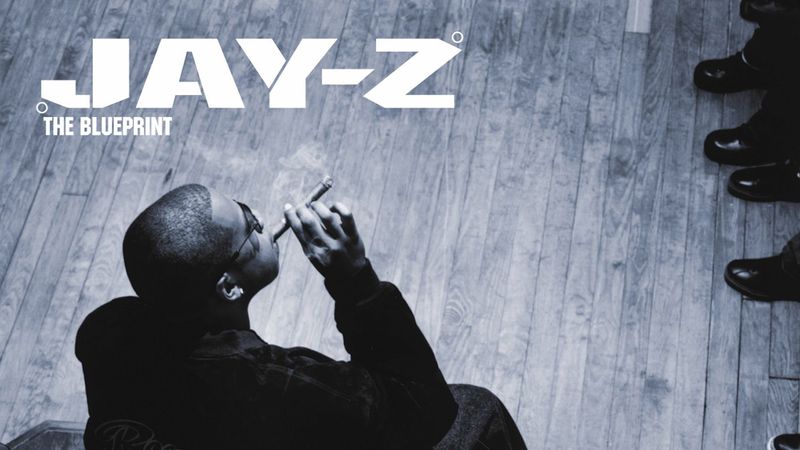

Released on September 11, 2001, ‘The Blueprint’ should’ve been lost to history. The world as we knew it was collapsing around us, yet somehow the album not only succeeded but made history of its own. It was Jay Z’s turn-of-the-century masterpiece, a monumental achievement that disrupted the tides of hip-hop and elevated a former crack dealer from the Marcy Projects to rap immortality and mainstream moguldom.

Now, nearly 14 years later, we hear the firsthand accounts of how the album was made, from its inception to its release.

Chapter 1: “The Ruler’s Back”

Lenny S (former director of A&R, Roc-A-Fella): I remember it was, like, two o’clock in the afternoon on a weekday, and Jay called me and was like, “Hey, are you in the bathtub right now?” I said that I wasn’t, and he said, “I need you to take a bath right now.”

Jay Z: I was at a point in my career where I’d finally made some serious money and it didn’t make sense to keep rapping about living in the projects. The next logical thing to do was to make some songs that would be nice to listen to at bathtime.

Lenny S: I called him back once I was in the tub, and he started spitting this verse like, “When I’m scrubbing myself with soap / I feel so nice and clean / But it scares me when the bubbles happen / How do they just appear? / Those tiny glass baseballs from hell?” He asked me if I thought it was a good bath song, and it got awkward. I didn’t know how to break it to him.

Jay Z: Lenny told me that Nas had beat me to the punch. He’d dropped a track called “I Don’t Fuck Wit Bubbles“ literally that exact same day.

Nas (rapper, Def Jam): It was sort of an arms race between us rappers to see who could land the first big bathtub single about bubbles, the round villains. And I wasn’t gonna let Jay come out on top.

Lenny S: I suggested to Jay that maybe this was a sign he should take a break from music and focus on his legal troubles. He was awaiting two criminal trials at the time—one for humiliating a police horse with a brutal freestyle, and another for organizing a parade to celebrate the death of Walter Matthau.

Jay Z: I didn’t care about the charges. Nas had disrespected me, and all that mattered to me was making something bigger and better than Nas’ bathtub music, something that could be listened to virtually anywhere in a house. I wanted to make songs so good that they would cause bees to halt mid-flight and start spraying out a new kind of honey that man had never tasted before—a richer, spicier kind of honey that they can only spray once in their lives, and once they spray it, they die on the spot.

Lenny S: Jay has always been convinced that bees have a better kind of honey that they’re hiding from us.

Chapter 2: “Gather Round, Hustlers”

Intent on recording an album that would redefine the rap genre, Jay Z carefully began assembling a crew of uniquely gifted musicians and producers to help bring his vision to life. He wanted to create a type of sound that diverged from everything else on the radio, something with a timeless quality that paid homage to vintage soul. He turned to hip-hop heavyweights like Slick Rick, Eminem, and Q-Tip, but he also recruited some relative unknowns, including up-and-coming producer Just Blaze and an obscure young beatsmith from Chicago named Kanye West.

Kanye West (producer, vocals): Before linking up with Jay, I was devoting all my energy to writing jingles about mail. I strongly believed that mail trucks should play music just like ice cream trucks do, and I thought that if I wrote a good enough jingle, maybe the U.S. Postal Service would start using it. There was this one jingle that went like, “If you’ve got a letter in one place / But you want it to be in a different place / Well, good news, mister / There’s this great technology called mail,” and for months I was just standing outside post offices singing it, hoping that someone from USPS would hear it and buy the rights. And then, one day, Jay just happened to be walking by while I was singing, and the rest is history.

Jay Z: I realized about two bars into that mail song that if I didn’t snatch that guy up quick, someone else would. So, I offered him 12 million dollars on the spot to come work on some tracks with me. Then, a day or two later, I hit up Blaze.

Just Blaze (producer): When Jay asked me to work with him, I was just a young kid with no experience in the industry, and I honestly didn’t know if I could cut it. But then he said something that really boosted my confidence. He said, “No one knows what happens inside washing machines, but we still put our knickknacks in there—you feel me?” And that’s basically been my motto ever since.

Bink (producer): I remember Jay coming to me and asking if I could make beats that sounded like the music that plays in his head when he’s holding two ice cream cones at the same time. And I was like, “How’s this?” and then I played him a little sample.

Jay Z: Imagine about 70 medieval trumpets screaming simultaneously but completely out of sync—that’s the sound I was looking for. Bink missed the mark, but I signed him on anyway. After that, I reached out to Em.

Eminem (producer, vocals, mixing): Jay had always been a mentor to me—he was the one who taught me how to use a microphone. For the longest time, I was tucking the mic into my belt and doing a sit-up every time I wanted to say a word, but then Jay showed me the hold-it-in-your-hand trick. So, I felt I really owed it to him to do a guest spot on his record.

Jay Z: I felt really good about the team I’d put together because all of them owned their own computers. It would’ve been really hard if we all had to share one.

Chapter 3: “So Off We Go, Let The Trumpets Blow”

Hova and his team started work on the album in early 2001, splitting time between the Manhattan Center Studios and Baseline Studios in New York City. The recording process didn’t take long—it was completed in only two short weeks—but it would yield some of the most inspired tracks in hip-hop history.

Just Blaze: Day one, we got into the studio and Jay had this big speech prepared. He said, “Imagine if you could take an X-ray of a house. You’d get a perfect snapshot of the lives of the people inside. You’d see their clocks, their ceramic frogs, their sleeping nests, their clocks—everything intimate would be revealed. Well, guess what: There actually is such a thing as an X-ray for a house, and it’s called a blueprint. Now, there’s no such thing as a blueprint for people, but if there were, it’d be this album. I want this album to be an honest snapshot of who I am from the inside out, which is a man who loves having nicknames and hates Nas.”

Jay Z: These days, there actually is such a thing as a blueprint for people. It’s called an ultrasound, but it only works on babies.

Timbaland (producer): After Jay’s pep talk, we all split off to start working on our beats while he jumped inside of a suitcase to write his verses.

Slick Rick (vocals): Jay always had a very methodical, one-word-at-a-time sort of approach to his lyrics. He’d write each word in the dictionary out on a separate notecard, and then, starting at A, he’d have someone show him each and every word until he found the one he wanted to use.

Young Guru (engineer, mixing): If he didn’t like the word, he’d ring his no-no bell 10 times. If he wanted to see the word again, he’d ring his no-no bell 11 times. If he liked the word, he’d applaud wildly and shout “Bravo! Bravo!” for many minutes. It was a time-intensive process, but you can’t deny the results.

Kanye West: The first joint I worked on for the record was “Takeover.” Jay said to me, “Yo, we’re gonna take down Nas with this one, so I need it to be brutal.” On my first pass, I got this children’s choir singing over a KRS-One sample on the hook like, “Return to sender / Return to sender / That’s what the envelope would say / If Nas were mail.” It was dope. Jay wasn’t digging it, though, so I switched it up to what it is now.

Jay Z: I was only gonna take shots at Nas [on “Takeover”], but then I decided to add a verse dissing Prodigy too, because I had a dream where he told me he would give me a ride in his hot-air balloon but then took his wife and daughter instead.

Eminem: Jay and I traded verses on this track “Renegade,” which is pretty heavy in my opinion. But initially, it sort of blossomed out of this freestyle we were having where Jay posited that there were probably a lot more things other than pumpkins that we could be making jack-o’-lanterns out of, which broke down into this call-and-response thing where I’d name an object that could be made into a jack-o’-lantern and Jay would agree with me. So, I’d be like, “A potato could work,” and then he’d be like, “I concur,” and then it’d keep going like, “A soccer ball could work”—“Indeed, it could!”—“A dead owl could work”—“I suppose you’re right!”—and later we both said our Social Security numbers. There’s a bootleg of it somewhere on the internet, I’m pretty sure.

Kanye West: The next joint Jay had me work on was “Izzo.” For that one, he asked me to imagine Biggie somersaulting down the streets of gold in heaven. He said I should go with whatever beat that image evoked.

Timbaland: Initially, I wasn’t even supposed to have a track on the record. The beat on “Hola’ Hovito” was actually something I’d made for Microsoft—it was gonna be the sound that played every time you created a new column in Excel. But Jay heard a cut of it and instantly started spitting this crazy-hot verse, and I knew right away I had to give it to him.

Bink: At the time we were recording the album, rap was starting to really embrace excess, so once we were done in the studio every night, Jay would take us out and treat us like kings. I remember one night, he rented out the entire VIP section of this club, and we each had, like, 40 chairs to ourselves. We couldn’t even sit in them all, so eventually we just started dumping them over the balcony, making it rain on the crowd. Shit was wild.

DJ Head (drum programming): Oh, man, those nights were insane. This one time, Jay paid the wrestler Kane $2 million to chokeslam anything we wanted for the entire night. He chokeslammed a guitar, a hot dog cart, a coyote, a mailbox, some traffic cones, a goose. Best night of my life, no doubt.

Jay Z: If we weren’t working hard, we were playing hard, and if we weren’t playing hard, we were floating around the sewers on a raft, searching for a half-man–half-alligator we’d heard about on the news. And that’s how we finished the album.

Chapter 4: “You Will Respect Me, Simple As That”

Despite its release coinciding with one of the darkest days in American history, ‘The Blueprint’ instantly became a commercial and critical success, soaring to double-platinum status and earning the reverential acclaim of reviewers everywhere. It cemented Jay Z’s position as the most powerful rapper alive and ushered in a new era of superstardom, in which a hustler from the projects could ascend to the top of the world without ever compromising who he is. Simply put, the album was a triumph.

Jay Z: I was just as devastated as everyone else when I learned about the 9/11 attacks, but I can’t say I was surprised. Reasonable Doubt dropped the same day as the TWA Flight 800 tragedy, In My Lifetime the same day as the Heaven’s Gate mass suicide, Hard Knock Life the same day as the U.S. embassy bombings in Kenya, Life And Times Of S. Carter the same day as Columbine, and The Dynasty the same day as the crash of Alaska Airlines Flight 261. I guess I’ve just got rotten luck like that.

Lenny S: Any adverse effect that 9/11 had on album sales was easily canceled out by the Eubanks bump.

Young Guru: If Kevin Eubanks endorses your record on his personal webpage, that pretty much guarantees you a half million album sales. He gave [The Blueprint] a rare five out of five smiles, and that alone probably pushed us past platinum. The guy’s a kingmaker.

DJ Head: It wasn’t until we went on tour that we realized just how huge this album was. I remember flying into Japan for a show and there were probably a million people waiting for us at the airport. The crowd swarmed the tarmac and picked up our plane while we were still in it and walked it over a hundred miles to this gorgeous, stadium-size marble structure. Now, over there they call Jay “Mr. Eternal Sad,” and we found out that this colossal structure was actually a mausoleum they’d built for him to mourn in.

Just Blaze: We went inside the mausoleum, and we found the prime minister and his wife lying ass-naked on this massive golden altar, and behind them there were probably 300 hunchbacks in Jay Z masks ripping their hair out and weeping. The prime minister invited Jay to light him and his wife on fire, and he didn’t want to offend them, so he did. As the flames consumed their bodies, they threw up the diamond and thanked Jay profusely until they burned to ash.

Kanye West: The success of The Blueprint meant nothing to me because it didn’t put me any closer to my goal of getting mail trucks to play my music. Wealth and fame are cancers. Art is a lie.

Jay Z: To me, the best part of having the album blow up like it did was probably the satisfaction of putting Nas in his place.

Nas: That diss track hurt my feelings so bad. When I heard it, I was so embarrassed that I lied down on the ground and didn’t move for three days. Then I got up, ripped off my nose, and fed it to a bird. After that, I felt fine. This is the first time I’ve thought of it since.

Jay Z: One thing people always ask me is whether I achieved my dream of making songs so good that they cause bees to spray out a new kind of honey. And the truth is that I don’t know; whenever I see a bee, I usually get nervous about its horn and shoot my gun until it goes away. But if I had to guess, I would say that those songs probably do make bees spray out a new kind of honey. The Blueprint is a pretty good CD, and there’s no reason why anyone—even bugs—shouldn’t like it.