In 1975, producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown took a chance on a young, relatively unknown director named Steven Spielberg to direct an adaptation of Peter Benchley’s bestselling novel, Jaws. Seasick crews, a ballooning special effects budget, and Spielberg’s naive perfectionism plagued the production and the studio began threatening to pull the plug. But out of all the turmoil rose a massive commercial and critical success which completely reinvented the Hollywood blockbuster, creating a template for big screen success that is still in use today. This is the oral history of Jaws.

Chapter 1: Just When You Thought It Was Safe To Go Back In The Water

Steven Spielberg (director): I was sitting on the beach I lived at one day when I saw a little kid around five or six years old just getting absolutely MAULED by a shark. It was the funniest goddamn thing I’d ever seen in my life. I mean this kid was just getting turned into hamburger, his eyeballs were spraying everywhere and his mother was trying to stab the shark with her beach umbrella but it just kept sliding off because sharks are slippery as fuck. I almost shit my pants I was laughing so hard. I turned to a horseshoe crab, wiped the tears of laughter from my eyes, and said, ”I want to make a movie about that, only even funnier.”

Peter Benchley (writer) [from a 1979 interview with Writer’s Digest]: I happened to overhear Steven’s conversation with the crab that day. He wasn’t a big director at the time—in fact, he was just this young guy who lived in a sandcastle at the beach who we all knew as “Crab Talker.” I walked up to him and I said, “Excuse me, Crab Talker, did I hear you say you wanted to make a movie about a shark?” He immediately stood up and walked out to sea, I assume to look for a shark.

Steven Spielberg: I wanted to get away so Peter wouldn’t hear the rest of my conversation with the crabs and steal my idea. Except I can’t swim at all, so I just walked into the water and kept walking on the bottom of the ocean as the water got deeper and deeper. I always say I became a director because I didn’t know how to swim, so there was no way I was going to be swimming professionally. But directing blockbuster films? Now that was something I could do.

Peter Benchley: I completely forgot about the shark attack and my conversation with Steven and his conversation with the crab, but I coincidentally happened to publish a book about a murderous shark a year later. Up until that point, every book or movie about sharks portrayed them as these cute little lovable creatures that would never smoke a cigar or wear punk sunglasses. There was this belief that you could push sharks around in baby carriages and dress them up in little gowns and they would never do any mean biting. My book was the first example in literature where a shark was shown acting like a pretty big dick. People would read it and be like, “A shark? A shark is doing all of this biting?” And I’d be like, “Mmm hmm!”

Richard D. Zanuck (producer) [from a 1985 interview with Cinefantastique]: I remember checking out the paperback of a new book called Jaws from my local pornography library. My son had been mauled to death by a shark about a year earlier, so I was always looking for ways to relive that trauma. When I saw the cover of Jaws with the shark on there with that big scowl on his face and that cigar in his teeth and those punk sunglasses, I thought, “This is a book.” After I read that book about Jaws and all of the mean biting he did, I did everything I could to get back at sharks: Giving them the stink eye when I saw one of them, spreading mean rumors about them, refusing to pick them up if I saw one of them hitchhiking—I was really trying to put them in their place. Then one day I had an idea. I called up the government and asked them if there were movies. When they replied “Yes,” I knew what I had to do: Become a hotshot movie producer and produce a movie about sharks that made sharks look like dicks. So I called the only person I knew who was actually friends with a shark: Steven Spielberg.

Steven Spielberg: One day I answered my sand phone and a very excited man on the other end blurted out, “The shark is named Jaws and he’s a mean shark!” I wasn’t quite sure what he was talking about, but I was intrigued. “I agree to do whatever you are asking of me,” I said, and we both hung up our phones and got some much-needed rest.

Richard D. Zanuck: Spielberg had a reputation as a guy who didn’t know a lot about directing movies and would take a leak in your wallet if you weren’t looking, but he lived in a sandcastle on the beach, so he knew a lot about keeping horseshoe crabs away from food. We had to take a chance on him.

Steven Spielberg: At that point most of my experience was in TV directing and talking to crabs. But with a huge budget and the support of a major studio, I knew this was my big shot. I was working 20 hours a day calling everyone I knew to ask if they had a shark we could borrow.

Richard D. Zanuck: You can’t make a shark movie without a shark, and we were running into a lot of dead ends because when word got out that we were making a movie that was going to make sharks look like dicks, no one wanted to lend us their sharks.

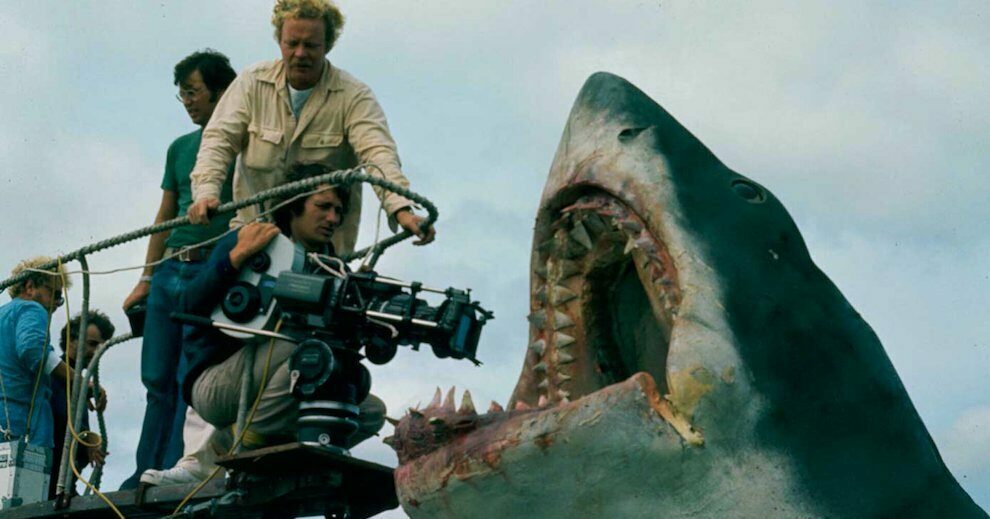

Robert A. Mattey (special effects) [from a 1987 interview with Fangoria]: Steven was new to directing, so he believed you had to borrow everything needed to make a movie. He’d say, “Go borrow me a shark,” and I’d tell him, “We can use a mechanical shark.” He’d just laugh and say, “Who are we going to borrow a mechanical shark from?” Finally, I took him down in my basement and showed him a prototype shark I was working on. It was a little rough because I had converted an animatronic human leg I had from a previous picture into a shark by spray-painting it silver. I said, “What do you think?” Steven looked at me like I was crazy, but then he reached into his bindle and pulled out a cigar and a pair of punk sunglasses. He stuck the punk sunglasses on the thigh and jammed the cigar between two of the toes. “Houston,” he said with a confident smirk. “We have a shark.”

Steven Spielberg: With our shark/human leg finally in place, the next thing we needed were some human actors. Most of them were going to be kids, of course, because you can’t make a movie showcasing the hilarious shark mutilations of over 30 children without a bunch of kids, but we wanted a few adults to get mauled by sharks as well, for scale.

Lorraine Gary (Ellen Brody): I originally tried out for the role of “Screaming Child Victim Number 18” but they said I could pass for a lot older than six so they offered me the role of “Screaming Wife Of Police Chief Number 4.”

Richard Dreyfuss (Matt Hooper): When I heard Crab Talker was making a movie about a mean biting shark played by a silver human leg wearing punk sunglasses and smoking cigars, I knew I had to do a solo sex scene in it. I called my agent and told her I wanted to try out for the role of Padlock Draper, the shark-hugging communist, whether or not that role existed.

Steven Spielberg: Richard was adamant that he play someone named “Padlock Draper” who was a “villainous commie who runs around hugging sharks and helping them eat capitalists.” I told him, “Look, pal, this is a movie about hilarious and incredibly realistic shark maulings of kids. You want to play this Padlock guy, go make your own movie, Dreyfuss. Now put my stingray wife down and get the fuck out of my sandcastle, it’s Hanukkah for God’s sake.”

Robert Shaw (Quint) [from his Jaws production diary]: Steven made the worst mistake of his life when he hired Richard Dreyfuss to be in Jaws. There’s a certain stench that I call “The Dreyfuss Rot,” and I’ve only smelled it two times: the time I discovered a boar had been dead in the trunk of my Volvo for two months, and any time I’ve been within a mile of Richard Dreyfuss. It’s not just a smell, it’s a curse. The Dreyfuss Rot permeated the set and corrupted the air we breathed, its sulfurous reek forever burned into our nostrils.

Richard Dreyfuss: Working with Robert Shaw was pure magic. We quickly became best friends. We were like Abbott and Costello or Laurel and Hardy. Just a couple of black-and-white goofballs getting chased around by a Frankenstein in an old haunted castle together, our friendship bulging larger and larger every day. Everyone called us “The Two Stooges” because of our black-and-white slapstick antics.

Lorraine Gary: For some reason Richard never caught on to just how much Robert hated him, despite Robert frequently bringing a gallows to work and shouting, “Hear ye, hear ye, today is the day we hang Richard Dreyfuss!” Richard would climb up the gallows and put his head in the noose thinking it was some kind of comedy bit between the two of them, and I’d tell him, “No, no, Richard, this man is actively seeking your death. You will be murdered by him soon.”

Roy Scheider (Chief Martin Brody) [from a 1979 interview with Playboy]: Robert would douse Richard with gas and light him on fire every day on set. It was a distraction, for sure, but Richard didn’t seem to mind. He’d say, “Hey, if I’m going to burn to death, what better place to do it than surrounded by such an incredible community making the greatest film ever made at the hand of my best friend.” And I mean, he had a great point.

Chapter 2: You’re Gonna Need a Bigger Budget

Spielberg’s insistence that the shark scenes be shot at sea as opposed to in a tank meant that the cast and crew were subjected to discomfort and danger not normally associated with a big studio film. The studio was tiring of the young auteur’s disregard for the film’s budget and the safety of the crew, but it was nonetheless becoming apparent to everyone involved with the project that they were making something truly special. So they soldiered on.

Robert A. Mattey: Jaws famously opens with a hilarious scene of a woman sitting alone on the beach at night who suddenly goes into labor. While she’s giving birth, the baby comes out a little bit and a shark in sunglasses comes up onto the beach and bites off the part of the baby that came out, and then she pushes out a little more baby and another shark who is smoking a cigar comes up and bites off that part, and this keeps happening until finally she pushes out the head and the head turns to the camera and says, “Hello, and welcome to Jaws,” and then the head starts crying really hard. That scene alone took 19 months to film. Steven kept saying, “Shoot it again, I’m not laughing hard enough,” and saying things like, “The baby doesn’t look munchy enough.” We had no idea what he meant by “munchy,” so we kept trying different things to please him. Finally, the actress playing the mother stood up to him and said, “Look, I can’t keep giving birth to all of these babies,” and Steven asked her why and she explained how pregnancy and birth works and he felt really terrible.

Richard D. Zanuck: From the beginning, the studio was furious at us. We were constantly way behind schedule, way over budget, and after five weeks of them asking where the footage was, all we could send them was a two-hour scene of Richard on a boat where he kept going off script and talking about his love for Robert Shaw and how they were going to be best friends forever.

Steven Spielberg: Let’s just say that the studio and I weren’t seeing cock to cock on a few things, money being the big one. They were just concerned about getting a return on their investment and I was trying to make the funniest shark mauling scenes possible where the mauling victim’s skin gets shredded into linguini while they’re screaming, “Stop biting me, I’m only in 1st grade!” and the shark bites into their bladder and you can see the urine spraying out and then the kid’s mom comes up and you think she’s gonna save him but she actually ends up helping the shark by holding the kid down and taking a few bites out of him herself. I was so focused on my artistic vision for these shit-your-shorts hilarious mauling scenes that I wasn’t exactly looking at a calculator the entire time to make sure we could “afford it” like some pussy accountant.

Richard D. Zanuck: At one point, we were $17 billion over budget. I tried to tell Steven, “The studio isn’t going to like this, they’re going to go bankrupt. People will lose their homes, their retirements. Thousands are going to go hungry because of this,” but then he’d show me the dailies of some little kid getting his nuts ripped off by Jaws and then his nuts grow back but Jaws eats them again and then another shark falls out of the sky and lands so the entire kid goes directly into its open mouth and then it just shows 15 minutes of the shark sitting there while we hear the kid’s muffled screams as he’s being digested alive, and we would laugh so hard that money just didn’t matter. In the culture we built on that set, laughter was the only money we needed.

John Williams (composer): When they came to me for the score, they only could offer me $12 in grocery coupons (mostly for onions, yum!) and a pretty big bag of sand because they were billions of dollars over budget. I quickly did the math and figured that it was worth about two notes, and the notes had to be pretty low and mean-sounding. I hummed, “Duh duh / duh duh / duh duh duh duh duhhhhhh,” and said, “There you go, suckers!” And I skipped off to the grocery to purchase my discounted onions while admiring my newfound sand. I never thought it would end up becoming my most iconic score.

Robert A. Mattey: Steven has always been a genius, but at the time we made Jaws he was very green to filmmaking. He wanted everything to be as realistic as possible, so instead of shooting the shark scenes on a set with a water tank, he insisted we shoot them in the actual ocean. Everyone was constantly seasick, always falling off the boat into the water and drowning because Steven insisted on hiring only cast and crew who couldn’t swim, and we were all malnourished because he was only giving us horseshoe crabs to eat for every meal. It was a lot of fun.

Richard Dreyfuss: It had always been a dream of mine to be super seasick and malnourished for months on end. Have you ever barfed dozens of times in an hour after eating nothing but raw horseshoe crab for probably a thousand meals in a row? I have. It’s Heaven.

Roy Scheider: Horseshoe crab is the one food that tastes wayyyyy better coming up than it does going down. It tastes like antelope smegma going down, but coming up it’s delicious. We actually begged Steven to let us stay out at sea longer so we could barf out more of them.

Steven Spielberg: All these guys wanted to do was barf. I had to keep reminding them that we were trying to make a movie here, albeit one in which barfing does play a major role, but not the only role. This was a movie about a shark with bad manners, not the delights of constant vomiting.

Lorraine Gary: Steven was adamant that the entire film be shot out in the ocean, not just the shark scenes, but the interior scenes, too. He had all these floating houses built out there, so we were getting seasick even when shooting the interior shots. If you watch closely you can actually see water gushing in through the windows of the houses and fish flopping all over the floor during every interior scene. That’s why everyone is always falling over and vomiting in the film.

Verna Fields (editor) [from her production diary]: Steven kept bringing me reels of film that were soaking wet and had barnacles all over them. I’d say, “What do you want me to do with this? It’s ruined,” and he’d say, “Edit the water off!” and I’d say, “You want me to edit the water off of the footage?” He didn’t even have a basic understanding of how editing works. Or towels, for that matter.

Chapter 3: Making Waves

While the cast and crew of Jaws were confident they were onto something big, the real test was coming. Would the American filmgoing public find repeated graphic shark maulings of children as funny as a cocky young director making his first major feature did? Was it worth 19 young lives and $17 billion in production costs? Luckily for everyone involved, Jaws was a smashing success.

Steven Spielberg: When Jaws first opened in theaters, Robert called me to tell me, “Uh Steven, uh Steven, you’re never, uh, going to believe this, but, uh, we sold a ticket.” A few minutes later he called and said, “Uhhhhh, Steven, we just sold another ticket.” Then it was three, then four, then five, then six…He ended up calling me 450,000 times in the next hour to tell me had sold another ticket, each time saying, “Uhhhhhhhh” a little longer.

Richard D. Zanuck: Our movie was everywhere. Jaws flavored Rolos. Jaws flavored toilet paper. Johnny Carson hosting The Tonight Show while getting mauled by sharks for an entire week. It wasn’t just a film. It was a phenomenon.

Richard Dreyfuss: When Jaws hit theaters, I learned for the first time what it truly felt like to be a star. I’d get strangers waking me up in the middle of the night asking me to wash their car. Women would push their way into bathroom stalls to flush the toilet for me. One time a baby saw me from across a swamp and he crawled all the way over to me in order to climb into the pocket of my pants and live there for the rest of its life. It was incredible.

Steven Spielberg: I went from living in a sandcastle with a stingray for a wife to having Hollywood producers show up at my house, literally get down on all fours, ask me to direct their latest project, and then melt into a steaming pile of goo that hissed out the word “Steven.” It felt so great to know that all of those mothers who were angry at me for killing their kids with a mechanical silver leg were wrong.

Leonard Maltin (film critic): Realmente puedes dividir el cine de Hollywood en dos secciones distintas, antes de Tiburón y después de Tiburón. Antes de Tiburón, su éxito de taquilla estándar era sobre un hombre que debe llevar un burro a través de una cancha de tenis durante Wimbledon mientras evita ser golpeado por pelotas de tenis para aplastar al presidente con él. Después de Tiburón, comenzó a tratarse de mostrar a los niños siendo lastimados atrozmente por animales como zorrillos, renacuajos y pandas.

Lorraine Gary: I made over $80 from being in Jaws, which at the time was the most a woman had ever been paid for anything.

John Williams: Before Jaws, when people heard a “duh duh duh duh” sound, they would just think it was the distant cry of a lost moron. Now, when people hear a “duh duh duh duh” sound, they think of Jaws. They start looking around for that shark that’s going to pop out of the water and devour their kids in an uproariously funny way. You can’t hear a “duh duh duh duh” without stopping and thinking, “Fuck, am I in the ocean right now?” Jaws may have changed how we look at filmmaking forever, but it also changed how we look at duh duh duh duhs.

Steven Spielberg: In a way, Jaws was the final wave goodbye to the old Hollywood blockbuster. It paved the way for Star Wars, Alien, and of course, my future work such as E.T. and Raiders of the Lost Ark. High concept, special-effects-laden films that brought genre film into the mainstream. Without Jaws there would be no Texas and Minnesota Come To Life To Fight Each Other or The Wheelchair Who Was In A Wheelchair. There would be no Ghost Gobblers. The Man Who Was All Bunions? Never would have happened. My vision for a knee-slappingly hilarious film where a silver leg is a shark and that shark is wearing punk sunglasses and smoking a cigar while doing mean biting on the small bodies of horrified prepubescent children while their intestines fall out and spell the words, “I’M SUFFERING,” was fully realized. If I was to do it over today, I wouldn’t change a thing.

Leonard Maltin: Si no amas Tiburón, no amas las películas.